Rhythmic Solfège

Translated by Robert M. Abramson

Foreword

Rhythmic solfège is not in competition with other systems of solfège. It is a complement to them, and an indispensable one. In fact, in the better treatises on the subject, classical or modern, the exercises are given with the sole intention of teaching the laws of pitch and meter, without introducing the subject of rhythm per se. Nor do they deal with the theory of rhythm (rhythmics) and its relationship with meter, dynamics, and melody. The theoreticians, while conceding that rhythm and meter are two different things, do not emphasize the distinction clearly enough, while the pedagogues give their students exercises in “rhythm,” so-called, which are simply exercises in simple metrics. There is without question a hiatus, confirmed by Berlioz in his work, “A Travers Chants,” which this author has the intention of filling.

Rhythm is an instinctive quality of the muscular and nervous systems. It represents a sort of compromise between force and resistance and frequently results in a change of, or loss of, equilibrium. The study of rhythm requires a whole series of special bodily experiences (experiments) which form an indispensable basis for the study of rhythmic manifestations on intellectual, sensory, and emotional levels. These experiences have been discussed thoroughly in my works on rhythmics.

Their application to vocal solfège will be facilitated by consulting these particular works. Music teachers wishing to experiment with this new form of teaching in their vocal lessons would do well to alternate the exercises in the first part (meter in double time) with exercises concerned with other meters.

Only the necessities of simplicity of classification made me decide to give the complete list of rhythmic exercises and their variations in 2/4. In practice, the teacher should apply progressively all these exercises to the study of 3/4, 4/4, etc. In general, he should adapt them to his teachings without being constrained to adhere rigidly to their order or quality.

He can ignore or simplify those which he finds too difficult and group others as he pleases. The only purpose of this new book is to help those who wish to introduce rhythmics into their teaching and to give them precise documentation and suggestions for further research.

Since the study of rhythmic solfège is not intended to usurp the teaching of standard musical theory, it constitutes, for the moment, a separate chapter in music teaching. The reader will not find the classical exercises in pitch, meter, or tone color which are part of the usual texts on solfège, nor a discussion of elementary musical theory. To the melodics in the present work could be added those in my three volumes entitled: Les Gammes et Les Tonalités, Le Phrasé et Les Nuances (Scales and Tonalities, Phrasing and Color). The teacher could also use any of the large number of rhythms published in my two volumes of Rythmique and in my Marches and Esquisses Rythmiques (Marches and Rhythmic Sketches), Jobin & Cie, editeurs, Lausanne, Rouart Lerolle & Cie, 29 Rue d’Astorg, Paris.

Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, 1905–1924

Part 1, Chapter 1: Rhythm and Meter in Two-Beat Time

Whole notes and half notes

Exercise 1: Subdivision of whole into half-half1

While the teacher sings or plays two whole notes in succession in any tempo, the student silently divides each note into two equal parts. Then he counts out loud “one,” “two” during the length of the teacher’s playing. Repeat this exercise in many other tempi.

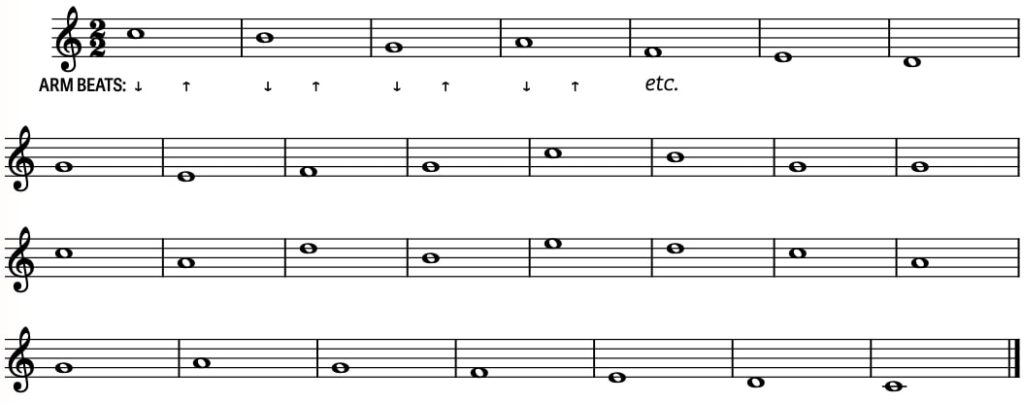

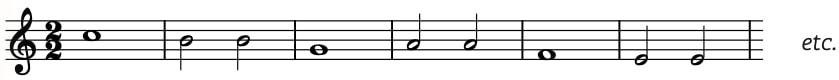

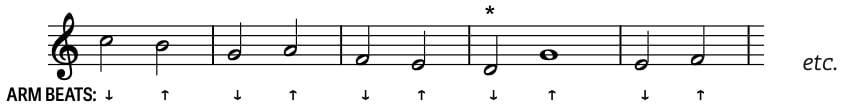

Exercise 2: Singing with arm beats in two

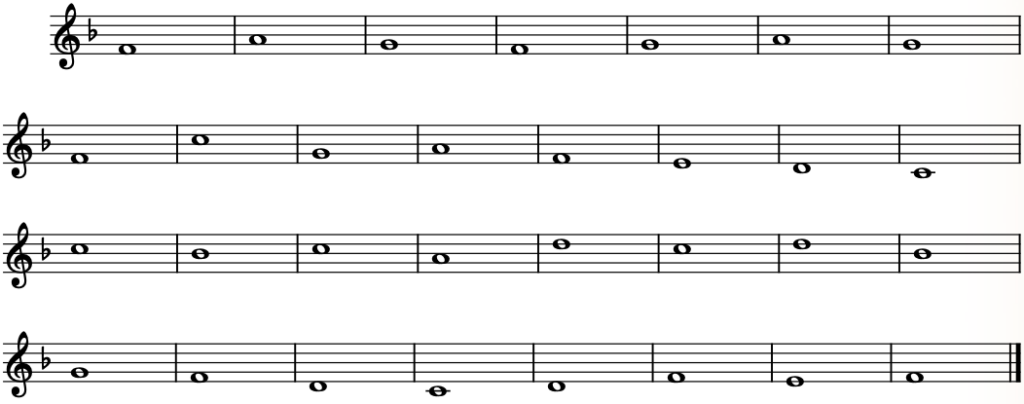

The student sings the following melody while beating in two-beat time.

Melody A2

Other melodies will be found at the end of the chapter.

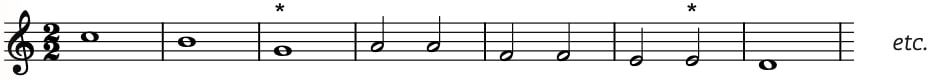

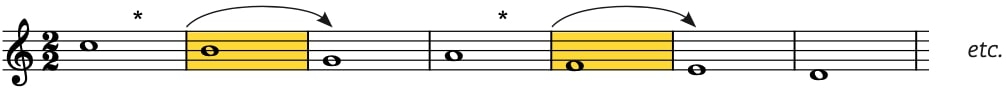

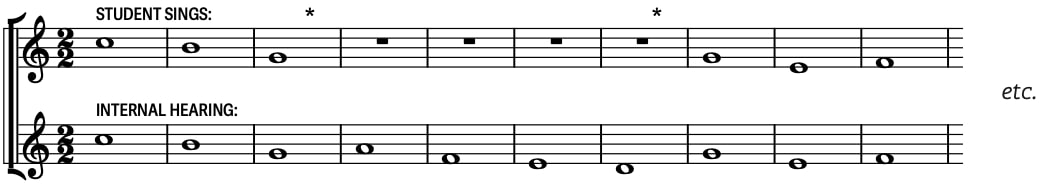

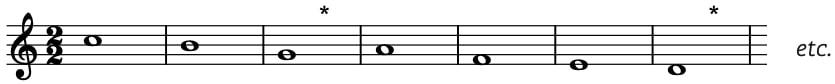

Exercise 33

The student sings the melody with arm beats. On teacher’s command (*), he repeats the note twice in the same measure (twice as fast) while continuing to beat. On the following signal (*), he returns to singing the notes as written.

N.B. The signal (*) is at first given so as to coincide with the note itself. Then little by little it is given closer and closer to the end of the measure in order to elicit quick reactions. The same procedure is to be followed for all subsequent exercises.

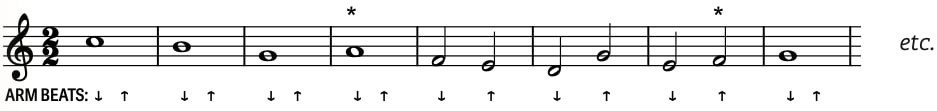

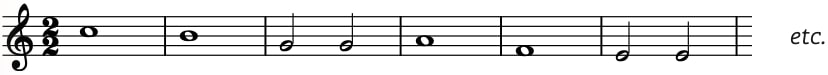

Exercise 4

On command (*), the student combines two measures into one without changing his arm beats, thus eliminating every other bar line and changing each whole into half.

Exercise 5

The student converts the whole note of every other measure into two half notes:

Or of every third measure:

(Or of every fourth measure, etc.)

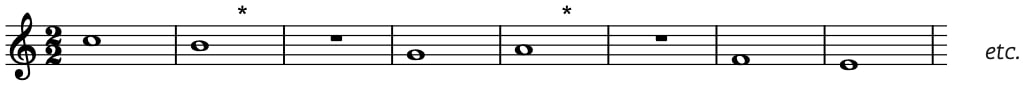

Exercise 64

On command, the student skips a measure, or 2 or 4 or more.

Skip one measure on command:

Skip two measures on command:

Exercise 7

On command, the student delays singing for one measure (or more).

Exercise 7a5

Alternatively, on command, the student immediately repeats the measure (or two measures).

Exercise 8

On (*), the pupil stops singing out loud but continues to do so internally (a) with arm beats; (b) without arm beats. On (*), he starts singing again.

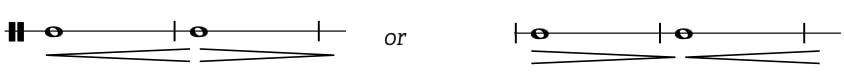

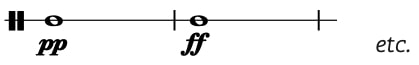

Exercise 9: Dynamics

The student begins:

a. The first note crescendo, the second, diminuendo and vice versa.

b. The first two notes crescendo, the next two diminuendo.

c. Or with various other gradations.

d. One note pp, the next ff or mf (and vice versa).

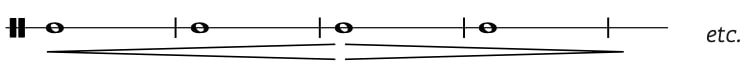

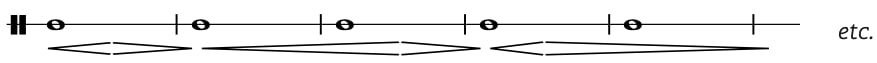

Exercise 106

The student sings the melody below, and on (*), sings the next note twice as slow. The arm beats also become twice as slow and twice as long.

Exercise 11: Phrasing

The teacher gives a signal each time he wishes the student to breathe. At the moment of taking a breath the student shortens very slightly the note he is singing.

Exercise 12

The student breathes according to a regular pattern, such as every four or every six measures.

Exercise 13

To obtain more lively vocal reactions and to diminish the “lost time” between the conception of a sung note and its performance, the teacher sings or plays the series of whole notes asking the student to repeat the note after him as quickly as possible. This exercise should be performed with and without arm beats.

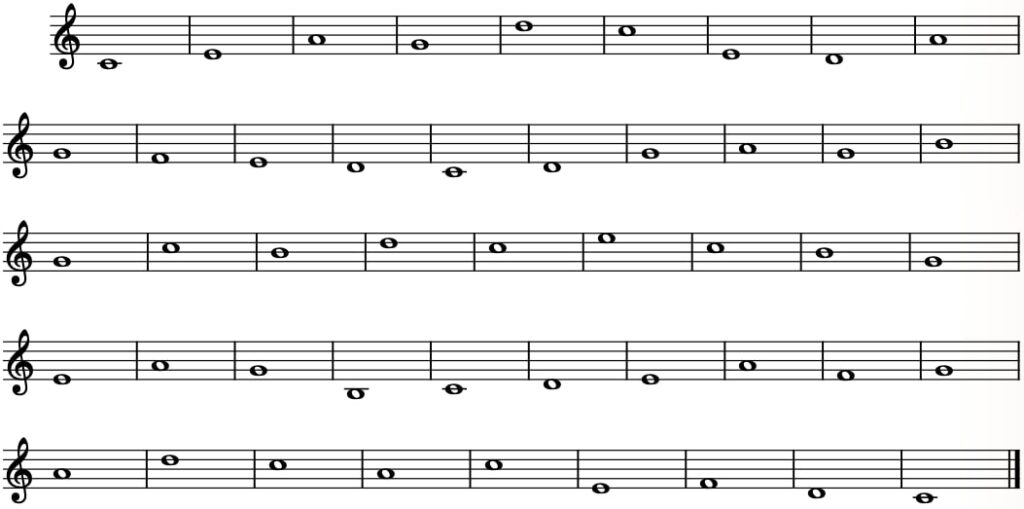

Other Melodies

Melody B

Melody C

This article was originally published in the Fall 2024 issue of Dalcroze Connections, Vol. 9 No. 1.

Commentary by Robert M. Abramson

- Notice that Jaques-Dalcroze always uses a preparation exercise before starting the class work. ↩︎

- This is not a melody yet. It will become one when the rhythmic games begin. This idea comes from an old technique for teaching composition. The student was given a series of pitches without tempo, meter or rhythm and was asked to create a melody. ↩︎

- The signals can be “now,” “change,” “hip,” “hop,” or “hup,” or numbers like “2” for twice, etc. It may interest teachers to know that I have used this material for instrumental practice in sight reading and dictation at the college level and also as an aid to instrumental improvisation, with excellent results and much praise from the instrumental teachers. ↩︎

- Educating the eye to scan the visual field rapidly. This is also a magnificent technique for testing your memory of a piece you need to perform and marks Émile Jaques-Dalcroze as a most remarkable learning theorist of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. ↩︎

- Another mind game for attention and concentration. ↩︎

- An excellent way of developing both vocal and instrumental technique as well as supplying attention to nuance, a quality now lacking in many of the movement, solfège, and improvisation classes I have observed over the last few years. ↩︎