Canons in the Dalcroze Classroom

When I was 8 or 9 years old, my mother had me listen to Franck’s Violin and Piano Sonata – she had just bought the LP and she thought I’d be interested in the 4th movement. We were the sort of family that was always singing rounds, but this was the first time I’d heard a round in classical music; I was delighted by it. How lovely to be able to hear the two instruments play tag with each other in this gorgeous, accessible piece. Many years later, in a Dalcroze workshop I attended, Herb Henke led a plastique animée to this piece, our arms reflecting the canonic piano and violin parts. The little girl in me still delighted in this; it was so simple and so rewarding.

Canons in Eurhythmics Classes

The canon form provides an excellent way into experiencing music, because it is simple to understand while its rewards take us into the complexity of layering music, that of counterpoint and harmony.

Dalcrozians know how challenging and fun are the traditional eurhythmics movement canons, where students step the rhythm of a measure (or any other predetermined amount of time) in canon with the teacher at the piano. Students need to quickly analyze and memorize what they are hearing, while stepping the patterns they’ve just heard. As a teacher, I get the kick of watching the physicalization of patterns I have just played while playing the next. Movement canons, these basic games of rhythmic counterpoint, are a staple of eurhythmics classes and assessments, and much more can be said. But this essay will concentrate on other aspects of teaching canons in a Dalcrozian way.

Introducing Canons to Children

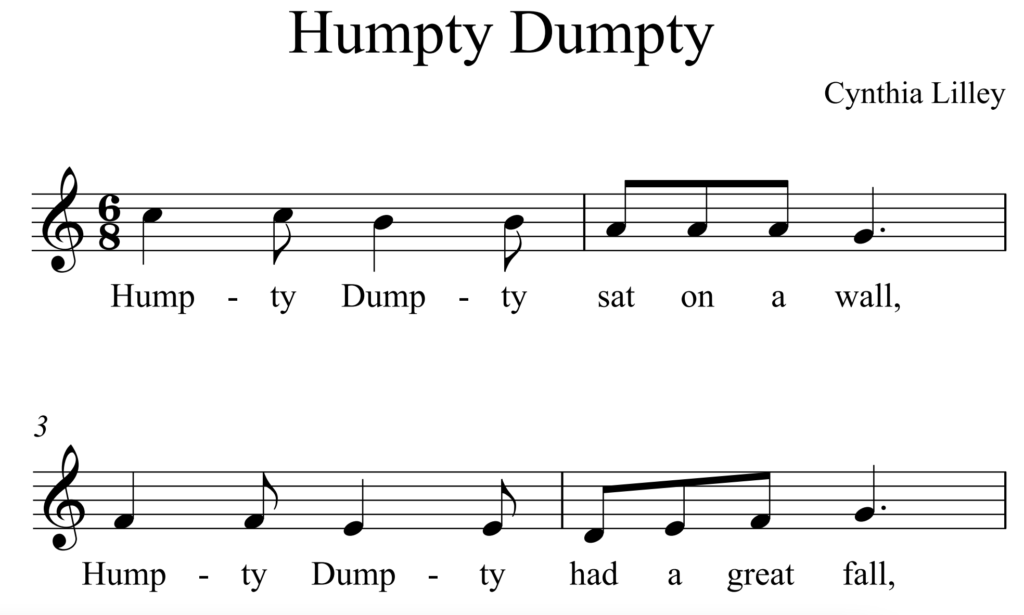

One of the first canons I like to use with children is my arrangement of Humpty Dumpty:

The students will have been working with the three primary rhythmic units in 6/8: beats, divisions, and the trochaic rhythm. Students move the units, put them in patterns, and identify them with the rhythm words, “beat,” “run-ning-and,” and “skip-and.” They also learn these as body percussion, with specific and unique gestures for each rhythmic unit.

Sitting in a circle, the students discover the patterns of the song through this body percussion system. Once that is properly automatized (one or two lessons later), we split into small groups and do it in (their first-ever) canon – with no melody at all, just the rhythm. It is a challenging but rewarding process, and less likely to confuse because singing isn’t yet involved. Soon after, the students learn to gesture the melody using Curwen hand signs, and eventually they are ready to sing the song in canon. And, voilà, they give voice to harmony.

Using Canons with Adults

I go through much the same process in teaching canons to older children and adults: by first having them experience and learn a piece through rhythmic movement and solfège singing in one large group. Once it is time to try the piece in canon, I typically have groups of students gently step the beat in place while they are singing in canon, which helps hold the meter together; then I have the groups move that stepped beat into space, letting them experience the kaleidoscope of different parts as other voices chance by.

Using Canons to Introduce Harmony

Many times, the pleasure of singing canons comes from this special way two or more parts intertwine, with the resultant harmony being experiential but not analyzed. But in adult classes, we can also delve into discovering and identifying the harmony that results from this conjunction of melodic lines.

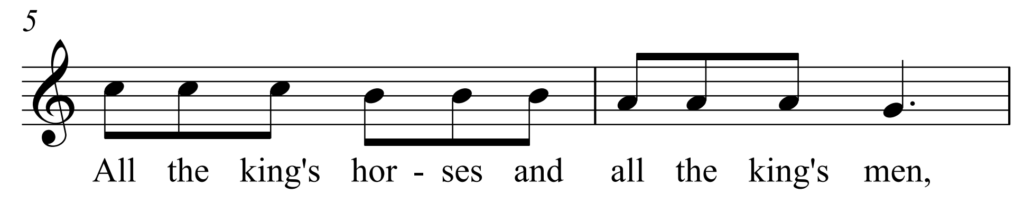

In beginning solfège classes I frequently introduce simple harmony with one-chord canons which are, of course I-chord canons. We start by segmenting a 1-to-1 scale into 3 sections: 1-2-3, 3-4-5, and 5-6-7-1, with 1, 3, 5, and 8 falling on strong beats and other scale degrees falling on weak beats. This quickly turns into “The Tonic Chord Canon,” which works because the tonic chord pitches all fall on strong beats.

We can find many examples of simple canons that work this way, such as “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” and “Three Blind Mice.” Not only can these all be sung as I-chord canons, but also those of the same meter can also be layered on top of each other in a type of quodlibet. I frequently assign students the task of composing their own I-chord canons for the class to sing. These can be very interesting, especially when rhythmic counterpoint emerges or when a non (tonic)-chord tone note falls on a strong beat, with resulting dissonance that gives just the right touch (or not)!

After this, of course, two-chord canons (usually I and V) can be dealt with – a slow “Frère Jacques” is a good example – and the students identify chords with hand signals. This can be further emphasized by using three or more groups, where one group sings just the roots of the chords and the other groups sing the song in canon.

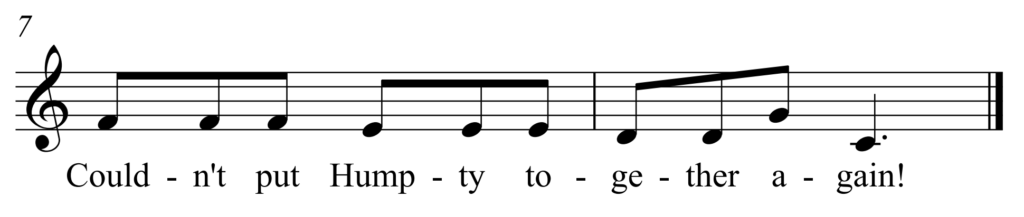

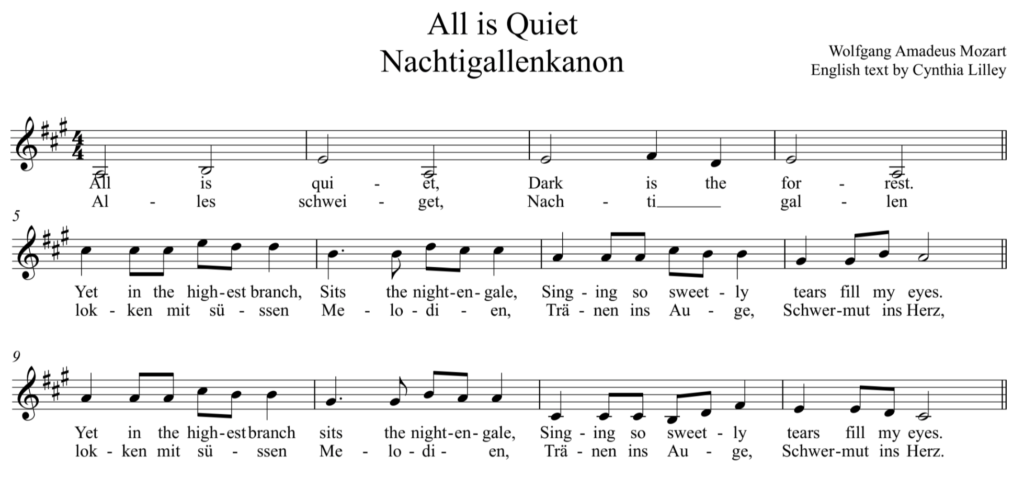

As we work with recognizing and manipulating various chords, canons that feature particular progressions are enormously useful in getting the sound quality of different chords into the students’ aural awareness. Mozart’s Nachtigallenkanon is a perfect example of I-ii-V-I:

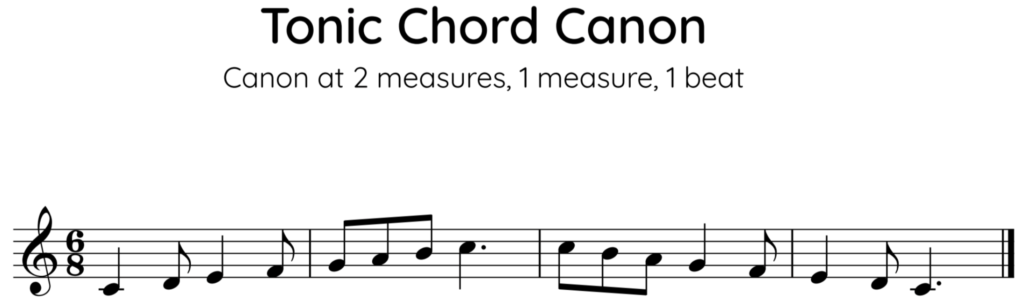

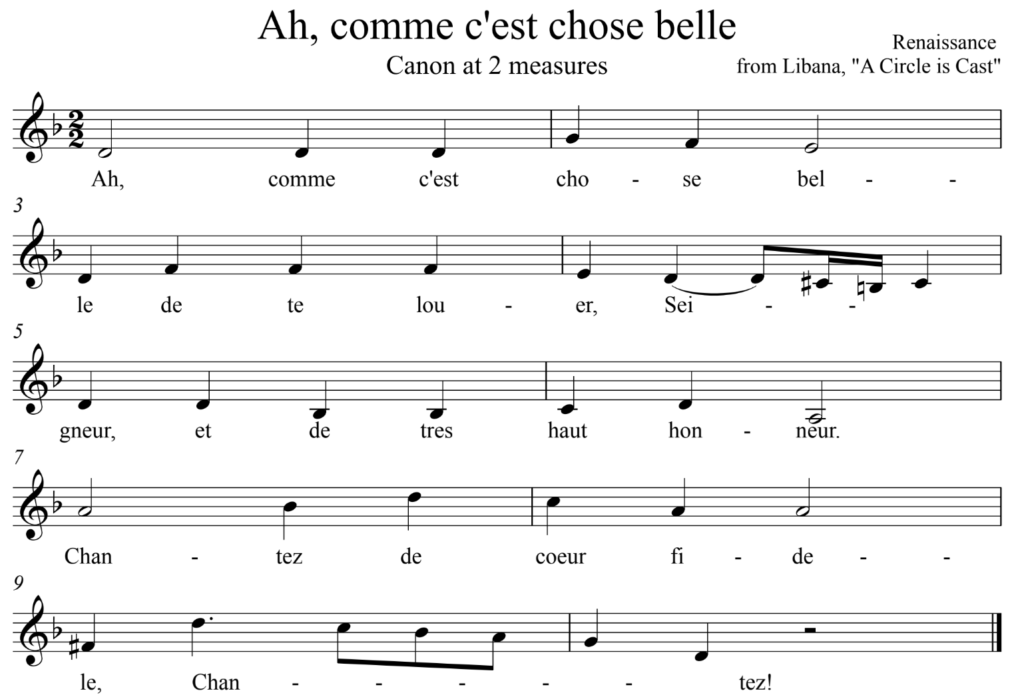

As students sing more complex canons, I like to have them be ready to stop and hold chords, identifying them by function and perhaps also by which voice of the harmony they are singing. One of my favorite canons for this purpose is “Ah, comme c’est chose belle:”

Canons at the Keyboard

As with much of solfège, these sung activities are further understood when transferred to the piano. In singing a canon, students are responsible for only one line at a time, but at the keyboard they get the challenge of putting these lines together by themselves. Playing a two-part canon between the left and right hand or treating a canon as a sing/play (playing in canon with the voice) are excellent ways to experience canonic counterpoint.

Improvised canons are also possible at the keyboard. With the use of two pianos, a fine time (and an ear-training challenge) can be had by having two students play in canon with each other, one improvising phrase by phrase while the other attempts to play the phrases in canon. This works especially well if using a small selection of predetermined phrases in an improvised order, or with a given chord progression. It is also useful to have a third person play a bordun or bassline in the chosen harmony to keep everything grounded. These types of games can also be particularly interesting when done in a church mode, which can yield fascinating harmonic modal proclivities (such as the Major II chord in Lydian).

Finishing A Group Canon

The teacher needs to decide how to end a canon. Typically, a two-part canon can be sung with Group A ending and then Group B ending alone. Or, the canon can be concluded as Group B sings the last line while Group A begins the first line. However, my favorite way to end – especially if students are moving in the classroom – is for me to give a visual cue (typically, a high hand gesture) to signal that each person comes to an ending at their own choosing, resulting in a serendipitous – and frequently pleasing – improvised finale.

Examples of Canons in Classical Repertoire

Examples of the use of canons in classical repertoire gives students examples of just how ingenious the great composers can be. The 3rd movement of Mahler’s 1st Symphony, with a minor “Frère Jacques” played in canon never fails to please young and old alike. The Minuet from Haydn’s String Quartet in D Minor (Op. 76, no. 2) provides a delicious example of the harmonic minor with its gnarly diminished 7th chords. The aforementioned 4th movement from the Franck Violin Sonata travels into beautiful harmonic territory via canon.

Other examples can be found which don’t comprise an entire piece or movement but rather happen within a piece and are worth isolating. Composers often use the related fugue within their works, starting a theme in two or more different parts of the scale; these play a very similar function as the canon and can easily be identified.

The fugue itself can be seen as a sophisticated outgrowth from the canon. Students who have immersed themselves in canons through singing, stepping, gesturing, playing at an instrument, and improvising, will be ready to tackle this most elegant of forms. But that’s for another essay.

Find more information about Dalcrozian use of canons on our website or let us know what other topics you’d like featured here.

Lovely to read and think about and sing along with!