Movement Training for Dalcroze Eurhythmics Specialists

My introduction to Dalcroze eurhythmics came when, in 1997, Lisa Parker hired me to teach movement in the Dalcroze program at the Longy School of Music of Bard College. In an effort to design a movement course that served Dalcroze students, I started taking, and immeasurably enjoying, all the eurhythmics, solfège, improvisation, and pedagogy classes I could. This was a unique setup in that I had a teaching role from the beginning of my Dalcroze learning and immediately infused what I learned into my teaching. My background is in both music and dance, and for my master’s degree in creative arts in therapy, I had rigorous training in Laban movement theory.

Dalcroze specialists need to be good movers. They need to be comfortable in their bodies, have enough energy, strength, and flexibility, and be relaxed enough to demonstrate and lead “good” movement throughout the day. They need to have excellent body awareness and be good “movement thinkers”: that is, they need facility at learning, remembering, creating, and executing movement sequences. They need to have an ample vocabulary of movement, both in their body language and in their verbal language, so they can talk about movement. They need to be articulate movers, in the sense of isolating individual body parts, moving combinations of body parts, and executing whole-body movement. They need to be articulate also in dynamics and in space. They need to be able to improvise, to have access to original movement motifs and ideas.

I drew from several curricular sources for the movement course. Two primary resources were the somatics training of Irmgard Bartenieff and Laban movement theory.

Somatics/Bartenieff Fundamentals

Somatics refers to practices and techniques that enhance the body-mind connection. These are techniques that can improve body awareness, posture, movement ease and efficiency in expressive and functional movement, strength, flexibility, and proprioception. There is a working together of body and mind, a sense of respect and even reverence for the body’s own intelligence, and a feedback loop of activity and rest, rather than a mind-over-matter approach.

Dalcroze eurhythmics and somatic education have much in common. Émile Jaques-Dalcroze himself wrote about the importance of training the student in muscular relaxation and breathing; he described exercises quite similar to the ones that have come to be known as “progressive relaxation” and “autogenic training,” well-known mind-body techniques that are applied in stress management and pain management treatment. He states, “The pupil is trained to reduce to a minimum the muscular activity of each limb then gradually to apply its powers. Lying on his back, he relaxes his whole body and concentrates his attention on breathing, in all its processes, then on the contraction of a single limb. He is then taught to contract simultaneously two or more limbs, or to combine” (Jaques-Dalcroze 1973, 65). He also states, “The aim of all exercises in eurhythmics is…to obtain the maximum effect by a minimum of effort” (Jaques-Dalcroze 1973, 62–63).

Example of somatic techniques include Bartenieff Fundamentals, Feldenkrais and Alexander Technique, yoga, Body-Mind Centering, Rolfing, and other types of body work, to name a few. New methods and approaches crop up frequently. For the movement course at Longy, I employed Bartenieff Fundamentals in part because Bartenieff’s work was heavily influenced by the work of Rudolf Laban.

Bartenieff Fundamentals teaches students how to move with efficiency of effort for the maximum of expression. This is accomplished through enhanced breath support, internal shaping, understanding of kinetic chains, and spatial intention.

Musicians often learn to breathe with the phrasing of the music and in support of the physical exertion when playing an instrument. Otherwise, they have the same result as dancers who “forget” to breathe: They lose expressivity and become stiff. This stiffness, if maintained chronically, can contribute to repetitive neuromuscular injury.

Sally Fitt writes, “Dancers who forget to breathe often look like frozen blocks because this inner shaping is absent . . . Breath enlivens and supports the full expressivity of the dancer. Without it a dancer is wooden” (Fitt 1996, 363). This also applies to the musician.

Kinetic chains refer to pathways of movement through the body. An awareness of the pathways of movement when performing an extension of the arm from the spine to the scapula to the hands leads to more integrated, fluid, and dynamic movement.

Spatial intention is an awareness of the space surrounding the body while performing a movement, with an intention of connecting with or reaching out into this space. This intention elongates the movement and eases the effort in the proximal musculature. The resulting movement is more relaxed and spatially dynamic.

Laban Movement Analysis

Arguably one of the most ingenious tools for working with the interface of movement and music is Laban movement analysis. Originated by Hungarian-born Rudolf von Laban (1879–1958), it is a comprehensive system and theory for observing, understanding, learning, notating, and talking about movement. Laban’s work revolutionized dance notation in part because it allowed for the description of the quality or dynamics of movement, which he called “effort.” In addition, Laban’s analysis of body architecture, also called “spatial harmony,” created a way to see, feel, and describe ways that the body moves in space.

Efforts describe the qualitative changes in human movement. These efforts exist in all human movement vocabulary. They also exist in nature and in the arts. Animals display certain, fixed combinations of these qualities, often in a very crystallized, highly refined form. A bird’s unique display of quickness with lightness, for example, allows for swift flight and escape from a predator.

Humans, like animals, have the potential to develop a wide array of movement qualities for both functional and expressive purposes. The artist, dancer, musician, and actor in particular need access to a range of movement nuance in order to express the various feelings, moods, and artistic intentions required in the art. Teachers, public speakers, managers, animal trainers, and many others in the business of communication also require a range of movement dynamics to be effective. The degree to which one is able to access a range of nuance in nonverbal communication contributes to one’s effectiveness as a communicator.

For Dalcroze students and teachers, understanding the three-dimensional space surrounding the body increases the tools for transferring sound into visible forms. An essential part of Dalcroze theory is the concept of “space, time, and energy.” This means that every musical moment takes a particular amount of time, a particular amount of space, and a particular amount of energy. The Laban “efforts” take the idea of energy and add a more descriptive component.

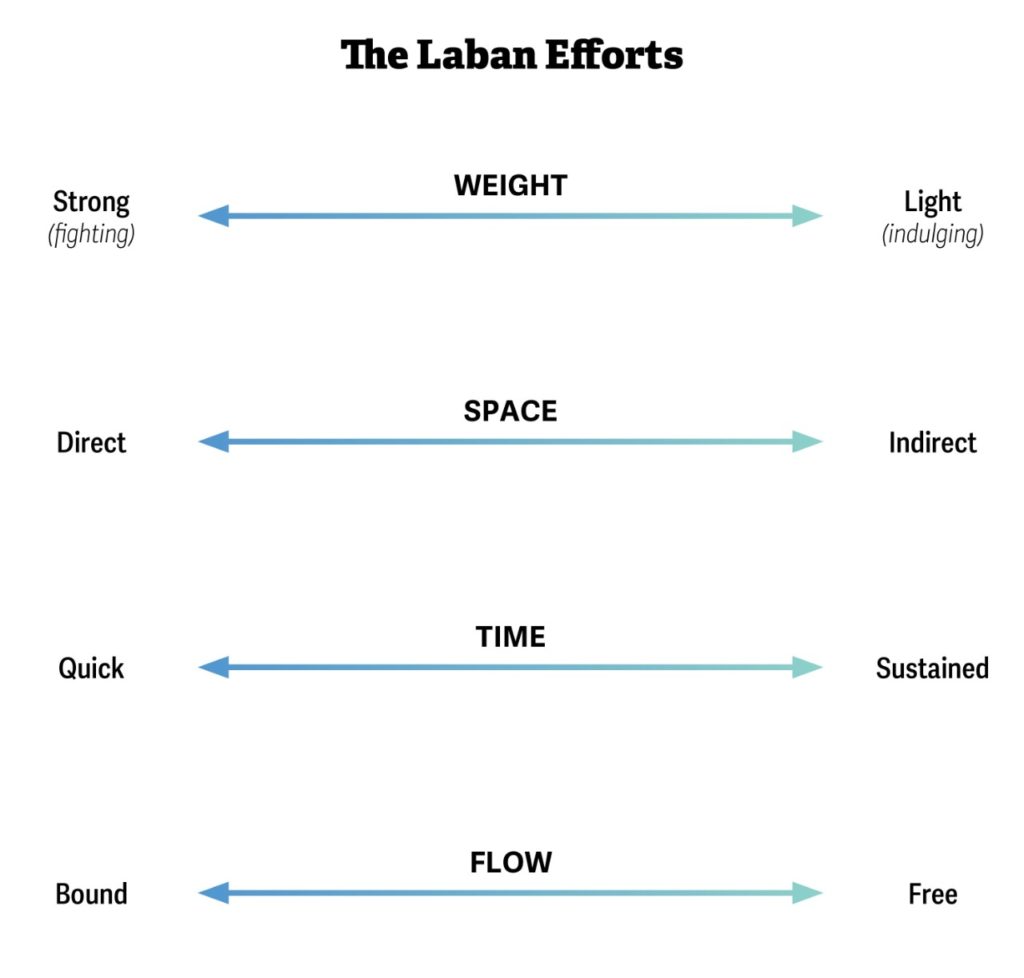

The Laban Efforts

The efforts as defined by Laban are weight, space, time, and flow. Each effort exists on a continuum from one extreme to the other, or from “fighting” to “indulging.”

Weight exists on a continuum from strong (fighting) to light (indulging). Weight has to do with the force of movement, with our muscular force. It also has to do with our relationship to gravity; in strong weight, we are pushing or pressing with force; in light weight, we are creating a feeling of antigravity or a feeling of buoyancy. Weight has a subcategory of passive weight, which includes the qualities of limp or heavy.

Space exists on a continuum from direct to indirect. If one moves with a direct attitude toward space, the movement has a clear and observable path and destination. An example is when one reaches out toward an object without any detours. A movement that is indirect is more meandering, taking multiple directions in its pathway. An example is when someone reaches out and feels the air for light rain or makes an “I don’t know” gesture by scattering both hands upward and outward. In music, direct space might be expressed with clear melodic or harmonic direction.

The effort time exists on a continuum from quick to sustained. Quick movement, in the “effort” sense, is not just fast but urgent. Sustained movement is not just slow, but it is very slow, like the slow motion of a film. It requires a lot of energy, a lot of effort to move with either sustainment or quickness. In fact, all the efforts require a lot of energy to perform because they are very concentrated qualities of movement.

Finally, the effort flow exists on a continuum from bound to free. Flow is about muscular tension. It is sometimes called “tension flow.” Bound flow is held and tense, free flow is unrestrained. Flow is intricately linked with the breath.

In the movement course at Longy, the efforts were introduced as a concept and as a skill. Students learn to refine their movements to express efforts in isolation and in combinations of two, three, or four efforts. For example, after practicing and conceptualizing about strong weight, the mover then combines strength with direct space, then indirect space, then free flow, bound flow, etc. Combinations of three or four efforts are called “action drives,” and there are eight: float, punch, glide, slash, dab, press, flick, wring.

Students were asked to discover the efforts in various music compositions. Music is often layered with several efforts and combinations of efforts, and discovering these can be an interesting and rewarding active listening experience. The piece Un Sourire by Olivier Messiaen, for example, opens with a feeling of the action drive “float.” Then a more directional melodic line is introduced, making it more of a glide. Following that, the percussion and strings introduce flicking motifs, and then these three action drives occur simultaneously, creating a rich texture.

The efforts identify more expressive detail than other language. As mentioned above, the word “energy” is often used in coaching music and dance. A teacher or coach might say that a musical or movement effect requires more or less energy to produce. When using effort language, one can specify what kind of energy is required. Does it need more strong weight? Does it need more sustained time? More lightness? More bound flow?

The efforts provide an invaluable language for describing and executing nuance in movement and for working with the interface of movement and music.

Works Cited

- Fitt, Sally. 1996. Dance Kinesiology. New York: Schirmer.

- Jacques-Dalcroze, Émile, trans. Harold F. Rubenstein. 1973. Rhythm, Music and Education. London: Dalcroze Society of America.

This article was recently reprinted in the Spring 2024 issue of Dalcroze Connections, Vol. 8 No. 2. It was originally published in the American Dalcroze Journal, Vol. 30, No. 2.