Association, Dissociation, Automatism, and Quick Reaction

“Clap the beat.”

“When I say change, change between your hands and feet.”

It’s not often that we encounter a eurhythmics lesson without hearing one of these quintessential phrases. They are an integral part of a eurhythmics class and an indicator that students are experiencing one of several frequently used pedagogical strategies: association, dissociation, or quick reaction. Each is a powerful teaching tool for the Dalcroze educator.

Association

when an element (musical or otherwise—a beat, a rhythm, a touch, or a gesture) occurs exactly the same way in two or more voices simultaneously

A teacher plays a pattern and the students clap it; student A draws a line through space and student B mirrors it; a class sings in unison while clapping the rhythm of the song they are singing. These are all examples of association experiences in a class.

Associations provide foundational listening and movement experiences for students; they are building blocks. After teaching college students for over thirty years, I know that students love demanding physical and musical exercises, but I’ve also learned that simplicity matters; associations provide simplicity. I use associations in multiple ways in a class.

To introduce a new topic

When teaching students who are experiencing eurhythmics for the first time, I use association between the piano and their stepping or clapping to introduce the beat in the simplest, most direct way, playing only what students will clap or step. This builds confidence and sets the stage for success while simultaneously teaching students that the piano provides structure and guidance in the class.

I often use the same technique when introducing a new topic; my goal is for students to experience a series of small successes as we gradually build to the big challenge over the course of a lesson.

To set the stage for a more difficult exercise

Imagine your lesson plan or long-term goal includes using a follow in class. My motto is “every good follow begins with a follow.” In a typical follow, students step a rhythm or pattern, and the teacher improvises over it with increasing complexity, using syncopations, hemiola, character changes, and other musical elements. Students need to hang on to the rhythm, stepping accurately and musically throughout the exercise.

I prepare students for successfully executing a follow by playing exactly what the class steps, first in a simple, pure way, gradually adding different dynamics, characters, etc., but still playing only the rhythm. This helps hone their listening skills and adjust to changes in tempo and character without added rhythmic complexity.

To expand a group’s movement vocabulary

Sometimes, students need ideas to spur their movement vocabulary, and I use an association exercise to lead them down a new path. Most often this is as simple as asking students to imitate a gesture I create. (Because the association is with gestures, I refer to this as a physical association rather than an association between a musical element.)

Eventually, I say, “Ok, you’re on your own,” or “Pair with a friend; choose a leader and copy what you see.” I then go back to the piano to improvise as they continue exploring.

Dissociation

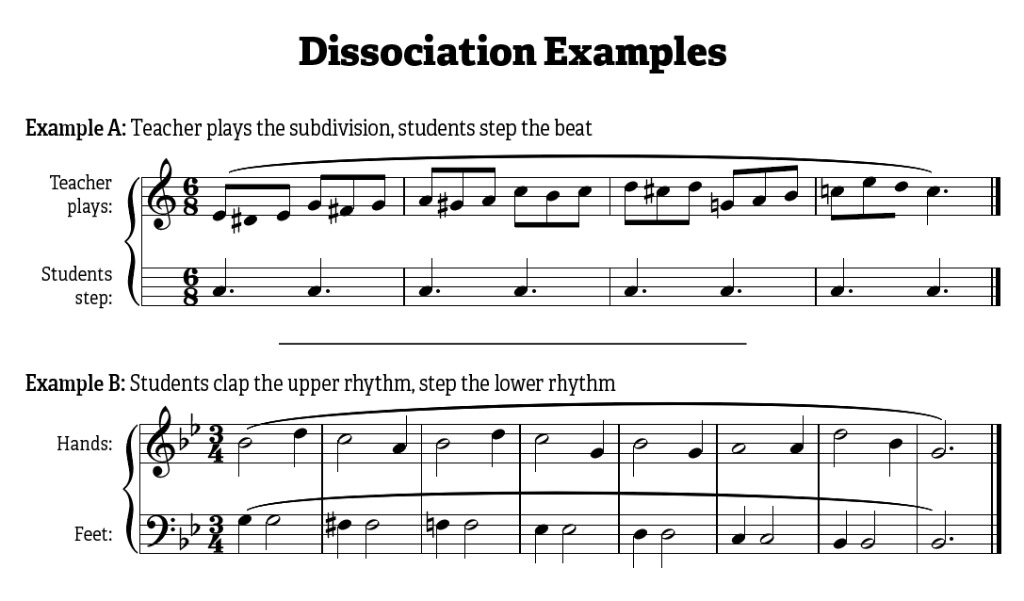

when two or more different elements occur simultaneously

The dissociation may occur between what I play and what students step (I play divisions, they step the beat, or I play triplets, they step divisions), between their hands and feet (they step the beat while clapping the multiple), or between a gesture they see and how they move (their partner’s arms may gesture overhead while theirs move out to the side). A dissociation raises the level of difficulty of an exercise, requiring more concentration and coordination from participants.

Experiences in dissociation encourage physical and aural awareness and are essential to high-level music making. We live in a complex, polyphonic world, and musicians need to develop the ability to perform their part while actively listening to the music happening around them. Jaques-Dalcroze offers this perspective in Rhythm, Music and Education:

One can imagine counterpoints of all kinds. The interesting and useful thing is to experience—live—them organically. Polyrhythm is facilitated by the cultivation of automatisms. An arm will execute a rhythm automatically while the mind executes the execution of a second rhythm by another limb.

Just as with association, I use dissociation exercises to teach a specific skill (e.g., beat/division/multiple) and also as a starting point for more complex exercises, like a quick reaction, canon, or follow. When using this strategy in class, it’s paramount for teachers to recognize that they have the power to either set students up for success or utterly overwhelm them. I work hard to ensure my students have enough experience with each element of the dissociation before I ask to combine them.

For example, we’ll clap and step the beat, then clap and step divisions; once this is comfortable (becoming an automatism), I may add a layer and ask students to clap the divisions while I play the beat, then switch between the two. Some classes need an additional step of pairing students, with each partner performing one of the rhythms (giving the added benefit of social interaction). Once they master each step—which may take three minutes or thirty, depending on the group—they perform the dissociation independently. Typically, I start with the more “solid” (most often slower) element in the feet and the quicker in the hands before asking the students to change.

Dissociation exercises turn from moments of challenge to moments of pure joy in a eurhythmics class, particularly when students are asked to perform complex dissociations. I remember well the first time I was asked to step amphibrach (a syncopated rhythm pattern) tempo primo in my feet and twice as fast in my hands. Despite careful preparation by my teacher, it seemed impossible! Eventually, as I mastered the skill, the sense of accomplishment and joy I experienced was palpable. I’ve watched the same transformation in my students over the years; I think it’s one of the secret rewards of our work.

Reassociation & Automatism

when a dissociation becomes easy—an exercise we can execute without effort or thought—it is a reassociation

A reassociation creates freedom and enhances the spirit of play for students of any age and level. It becomes, in fact, an automatism, something we can execute completely without thinking, often while focusing on or simultaneously performing something else. Simply put, automatisms are the Dalcrozian’s answer to multitasking. Automatisms allow us to shift our focus from one task to something new or more difficult and to trust our physical capabilities.

Do I use automatisms in class in the same way I use other strategies? No. Mostly, they are something I observe, a sign I can challenge students with a more difficult exercise. But I can’t imagine executing many other exercises—a dissociation, ostinato, canon, polyrhythm—without the benefit of an automatisms.

Jaques-Dalcroze understood the vital role automatisms play in our daily lives. In Rhythm, Music and Education, he wrote, “The better our lives are regulated, the freer we become in every way. The more words are included in our vocabulary, the more our thought is enriched. The more automatism possessed by our body, the more our soul will rise above material things.”

Eurhythmics students work to automatize the Dalcroze arm beats in 5. Photo by Kathryn Nockles.

Quick Reaction Exercises

If there is a classic exercise in the eurhythmics experience, the quick reaction may be it.

I remember my first eurhythmics class when my teacher said, “And when I say ‘change,’ you’ll change between hands and feet.” My eyes got big and I thought, “You want me to do what?” I never thought this was a skill I could master, and certainly, in that moment, I never realized how much fun quick reaction exercises could be. Musicians need to be flexible, ready for change, and prepared for the unpredictability of performance. Quick reaction exercises serve to develop these skills while allowing teachers to reinforce new concepts and build the level of challenge in a class.

In a quick reaction exercise, the teacher uses a signal to motivate a change in movement through one of four means: verbal, aural/musical, visual, or tactile. Each challenges students differently and develops other skills, such as listening, coordination, and concentration, in various ways.

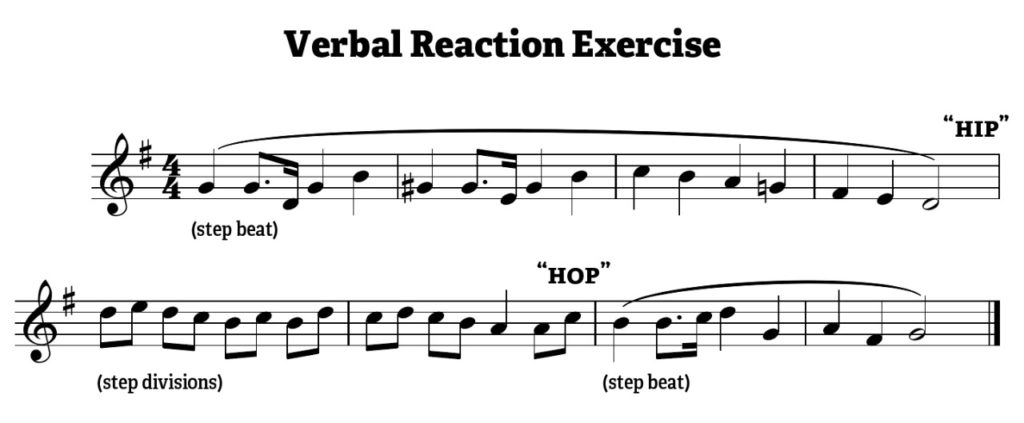

Verbal Quick Reaction

Here, the teacher (or a student) gives a verbal cue (“change,” “hip,” “hop,” etc.) to stimulate change. The frequency of the signal is one component that determines the level of difficulty of the exercise. When I’m introducing a topic, I may signal change at the end of a phrase; as students master the skill, I increase the frequency to add a layer of difficulty.

One of my favorite things to do in a class is to choose an interval (each measure, for example) to say “change,” to set up a habit, then change the interval at which I give the signal. Invariably, students have been lulled into believing the pattern will last forever and get surprised by the sudden lack of change! It’s always a great reminder for them of how musicians can’t stop listening, thinking, and reacting. Unpredictability is fun.

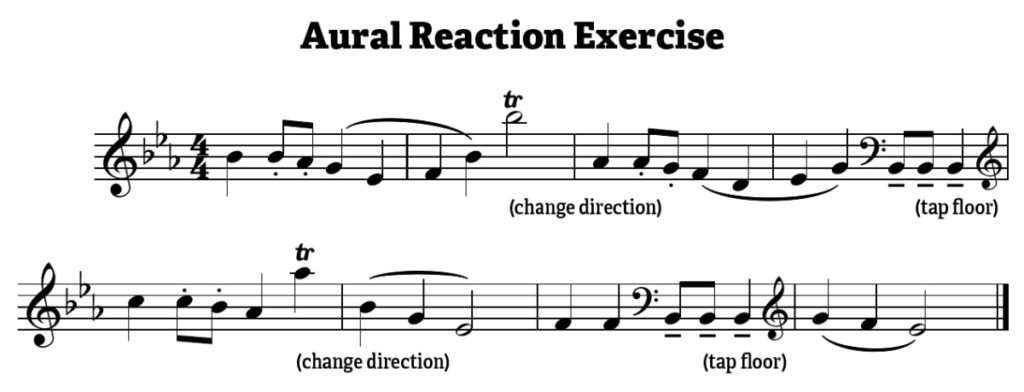

Aural/Musical Quick Reaction

Laced into the teacher’s improvisation, an aural quick reaction uses music to signal a change. An easy example of an aural reaction is playing for a locomotor skill—a march—then changing to another—a skip—using only the music as a guide. No words!

The possibilities are endless: Music in major may indicate stepping forward; in minor, backward. Three notes played in the bass might indicate tapping the floor; a trill in the soprano means turn around or change direction. Aural reactions are fun and help develop listening skills.

Visual Quick Reaction

Here, students need to watch the teacher (or a partner) to execute a change.

The teacher might tap beats on their head, and students imitate. Then the teacher switches to shoulders, then knees, and students make each change with them.

A more challenging visual reaction might use gestures to indicate specific rhythm patterns. For example, in compound meter, arms overhead indicate divisions; arms extended down, the beat; out to the side, a skip; and in toward the chest, short-long. The class claps or sings the rhythm as the teacher moves between patterns; a student could lead the exercise while the teacher plays, leading to interesting experiences with phrasing and cadences. To add another layer, split the class in half. One group watches the right arm; the other, the left, and magically, the quick reaction also becomes a dissociation exercise.

Visual reactions can be helpful to change the pace of a class, or to use when the teacher feels a need to be with the group physically rather than at the piano. They provide opportunities for students to lead an exercise. They also help students learn to “hear” music in their heads when it’s not being provided for them, enhancing their musical imagination and providing a pathway to improvisation.

Tactile Quick Reaction

Here, the signal for change is indicated by touch. This may be the least frequently used type of reaction, but, like an aural/musical cue, is an effective way for teachers and students to communicate without words.

Imagine students seated in a circle. One person walks around the outside of the circle. If they tap someone’s head, that person claps the beat; shoulders, divisions.

Another possibility: in pairs, one student taps beats (or a pattern) on the shoulder of their partner, who responds by clapping, articulating, or improvising a melody in rhythm.

A fun exercise is to place students in a line. The student in the back taps a rhythm on the person in front of them, who does the same to the person in front of them; when the teacher says “change,” everyone turns around and the rhythm “changes” direction. Warning: silliness can easily ensue!

Placing the signal to change is essential to successful execution of any quick reaction exercise. Give the cue too soon and students may try to change before it makes musical sense; too late, and the teacher sets the class up for failure. When I execute a quick reaction in class, I think anacrusically so that placement of my signal aligns rhythmically with the musical element.

Closing Thoughts

Association/dissociation and quick reaction exercises are closely related: an association may quickly turn to a dissociation as the teacher starts to improvise over a rhythm and layers a new skill; that dissociation may then become the basis for a quick reaction exercise. These strategies teach listening, coordination, concentration, and memory and are a valuable asset in a eurhythmics teacher’s cache.

References

- Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, Rhythm, Music and Education, trans. Harold Rubenstein (Ashford, Kent: The Dalcroze Society, 1967), 70.

- Jaques-Dalcroze, 61.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2023 issue of Dalcroze Connections, Vol. 7 No. 2.